Shibboleth

Here, starts with a window.

Because when the dog days were drawing to an end the narrator of W. B. Sebald’s “Rings of Saturn” admits himself to a hospital in Norwich in a state of complete exhaustion. Bedridden on the eight floor all he can see from his debilitated position is a colorless patch of sky framed in the window. Suffolk's expanses, which he’d been exploring for the past year during the novel’s titular “English pilgrimage”, have now shrunk once and for all to a single, blind, insensate spot.

Draped for some strange reason with black netting, the window is both the beginning, and the end of the narrator's story. Whereas, according to the novel’s chronology, it appears after the journey recounted in the book, therefore can be seen as a symptom of the narrator’s despair. But for us, the readers, it manifests at the start, and therefore can be interpreted as its cause.

Because who’s to say what comes first: a window, or the egg?

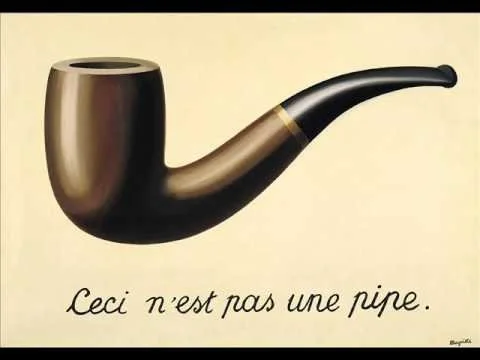

Observed from an uncomfortable angle, the window resembles a canvas perched on an easel, and like Rene Magritte’s famous painting “The Human Condition”, seems to suggest, there is no evident difference between reality and representation.

With great reluctance and unease, the narrator slides off the bed, drags his catatonic body to the windowsill, and leans against the glass in the tortured posture of a creature that has raised itself erect for the first time. He fears the world outside had completely disintegrated, and is compelled to prove its the existence by looking out the window. He compares himself to Gregor Samsa from Kafka’s “Metamorphosis”, who after changing into an insect looks out the window no longer remembering (so Kafka's narrative goes) the sense of liberation that gazing out of the window had formerly given him.

The world ‘outside’ had become a wasteland, an utterly alien place. The connection between his inner image of it, and the factual referent is sutured (or, at best, entangled). Although suspended in one another, they are doomed to remain isolated. All I could hear was the wind sweeping in from the country and buffeting the window; and in between, when the sound subsided, there was the never entirely ceasing murmur in my own ears.

I read “Rings of Saturn” on a night bus to Dharamshala. I always take it with me when I travel. Like the narrator I too look out the window to prove something. But contrary to him, it is not the outside world I need to validate, but my own existence. Then again, what’s the difference?

Mahogany shifts into pine, birch collapses into juniper; a beautiful green hill for a split second turns into a brightly lit convenience store but quickly morphs into a heap of garbage left on the side of the road to rot. Himachal Pradesh is said to be the fruit bowl of India, filled with widespread orchards and crop fields. I see non, the panorama exclusively consists of dried up pastures desperately clinging to steep mountain slopes as if afraid to let go in case everything collapses. The hope it does, entertains me on this long and beautifully boring journey.

As the landscape outside runs away in pieces and parts, I am reminded of a different scene in Kafka’s story. After Samsa’s transformation his mother and sister decide to make more room for him, and dispose of all his possessions. But he doesn’t want more room! He wants his life back! And so he jumps on a painting just as it’s taken away. He clings to the picture with his tiny insect legs as if wanting to merge with the image inside. But the cold, slippery glass securing the picture can’t be gripped. He slides off falling into the void of being something, he doesn’t want to be.

The word tableau traditionally refers to a graphic description, or pictorial representation. But according to Antoine Furetière’s XVII century architectural definition, it can also point to any opening in a wall that illuminates a room, such as a door, or window. And so, on the eve of a new millennium the Canadian photographer Jeff Wall takes pictures of three windows. All three are blind. The images both oppose and fit Furetière’s definition. They are anti-representations, or failed images, as if the artist wanted to show how a photograph of a window not only projects our seeing, but also, inverts it. His blind windows visualize that, which in any other circumstances would remain hidden. The unseen emerges like the pressure of the unspeakable which wants to be spoken (R. Barthes, “Camera lucida”).

Wall’s pictures present windows covered from the inside making them reflective like mirrors. But the epidermis of reflexibility is scarred, so in fact, they aren’t mirrors, but their underbellies; that what we find beyond the looking glass. Two of the windows are cut by wooden beams and planks making them unapproachable. They look like cages. Should we fear what is inside, or the other way around? They become grids.

The third picture is a basement window (or worse), taken from a strange angle as if in a hurry; cropped in such a way that it feels claustrophobic. The frame is morbidly green and disproportionally heavier than the painted black glass which it supposedly holds up. So in fact, it weighs it down. The point of the image, the window itself, vanishes. The frame becomes the event horizon of the imagined. Whatever was behind it (or maybe still is), has since been utterly forgotten, the meaning has been buried alive.

Wall exhibits the blind windows on light-screens which further complicates their significance. Because, although thematically they represent the dismissal of light, their very existence is built on it. But the lucidity becomes tainted forcing us to re-examine the notion of transparency all together.

The conventional idea of representation as transparency (and later: photography as fact) derived from the Renaissance concept of a window (painting) through which we witness objective reality, is flipped inside out, collapsing alltogether “through a glass darkly”. It possesses us, pulling down to the dangerous void of representation and understanding, forming a grid which essentially traps both the seer and the seen in the helpless detachment of a frame.

Through the simple gesture of covering up a window, as one should a mirror in a house where someone had died, Wall shifts the meaning of the medium from that ‘through which we see’, to that ‘what we see’. But his approach is much more subtle and insidious than your average MaCullian ‘medium is the message’ dictum, because the windows become referents that point only to themselves. There is nothing in front, or behind them. Both the viewer and the subject disappear. The image looses its content and context becoming a fetish, a closed circuit looping its own meaning. Wall’s windows are a phantasmagoric display of focalizing blindness. We don’t see, what we see.

Here, space and time stop, the viewer is sucked in to the event horizon of witnessing and understanding, and nothing can escape that pull.

This is where I look for my home.

Because ‘here’, doesn’t really start here. It starts on a beautiful summer afternoon in California when my father announces that my mother is dead.

In 1915 the German physicist and astronomer Karl Schwarzschild provided the first exact solution to Einstein's theory of general relativity. His proposal was outrageous and precise, it perfectly described the manner in which the mass of a star deforms the surrounding space and time.

According to Schwarzschild's calculations, when too much mass is concentrated in a very small area, as occurs when a giant star exhausts its fuel and begins to collapse, space-time doesn't simply bend, it tears reality apart from the inside. The star keeps on compressing, and increases its density until the force of gravity becomes so powerful that space curves infinitely, and time closes in on itself. The result is an inescapable abyss permanently cut off from the rest of the universe, an absolute void.

The theory was later called 'Schwarzschild singularity', and to this day, is the only accurate way to explain the workings of a black hole.

At the centre of a dying star, all mass becomes concentrated in a single point of infinite density which threatens the very foundations of physics. Whereas, within the singularity, the notions of space and time become meaningless. Inside the void, the fundamental parameters of the universe switch properties: space flows like time, and time stretches like space, causing a distortion that alters the laws of causality.

If a hypothetical traveller could reach the centre of the abyss, without gravity tearing her apart, she would distinguish two superimposed images projected at once in a small circle over her head. In one, she would perceive the entire universe at an inconceivable pace, while in the other, the past would be frozen in a never-ending instant.

The void is surrounded by a limit, a barrier that marks a point of no return. Any object, no matter its size, would be trapped there forever, as if it had fallen into a bottomless pit. But the singularity itself is a blind spot, fundamentally unknowable, because light can never escape from it, therefore our eyes are incapable of seeing it.

This point of no return has no signs or demarcations, it sends no warnings. You would never know when you crossed it.

Years before revolutionizing astrophysics, Schwarzschild developed a formula known as “the Schwarzschild law” which calculated photographic material density, the degree of blackening or darkness in a developed image which is a measure of how much light is transmitted through the film.

So instead of a memoir, allow me an image. In the form of a courtesy. Like a professor during a lecture who says: please allow me to change the subject. Or a vampire asking to be let in at night, a captive chained in a basement begging for freedom. Allow me to live, even if I die. Allow me a sense of relief. Allow me a flash of reproduction, sharp as a needle, and nauseating from the smell of magnesia. Allow me a painful exchange that sharpens the edges of things, but blurs their significance. Allow me a dangerous seance ruled by hungry ghosts where the contours of shapes fade like in a coloring book that lost its lining, and nothing is as it seems.

Let’s make a memory, my mother says pushing me inside a photo booth at the central train station in Gdansk. I don't understand what is happening. I am scared, and don’t know what memory is, or how it can be made in this tiny room smelling of wet dog.

She embraces me, a little too forcefully, but I don’t mind, this is how we relate.

I am restless, my inexperienced three year old mind senses that nothing good will come out of this ‘memory making’. But I haven’t learned how to scream yet, so I succumb. She is tenuous, and anxiously holds me close as if afraid the camera will steal me. Or maybe, she fears for her own safety? In that moment, I become her anchor, stuck to the bottom of the sea watching her underbelly carelessly float on the surface. She is beautiful, sun-soaked, and dead, even before she actually is.

I am alive, but unable to live.

Hold still, and smile when the little round piece of glass flashes, she whispers in my ear as if the possibility of moving away from her had ever been an option, as if I wasn't pinned down by our love like a butterfly in a collection. As if, I was free to explore where I end, and she begins.

Hold still.

She gently cups my chin in her hands and pushes my face towards the lens.

Cheese, she shrieks kissing me on the cheek, but in Polish, so there is no cheese to speak of.

And just like that, it's done, we become a memory, and for the rest of our lives together are unable to become anything else.

Allow me image. Allow me regret. Because what is an image, if not contrition?

My mother looks angrily at the camera as she stands above a sink full of dirty dishes. She is very young, bold and beautiful, a woman that only recently had come into possession of her woman-ness. She is power. She is fear. She is on a summer camping trip with friends. I can almost hear them drunkenly laughing in the background. She’s wearing a black pullover, and tight jeans. Her eyes are mean, and fiercely intelligent.

This is her, before there was a me to reference. A black and white alternative, a snapshot of how her life would have played out, if I’d never been conceived. Here, I can find the face I had before I was born. It is beautiful and absent, just the way I always wanted to be. “I read my nonexistence in the clothes my mother had worn before I can remember her." (Barthes, “Camera lucida”)

Here, everything is peaceful, because I don't have to remember her, because there is no me to do the remembering.

I wish I could live in this photo forever, not existing, only slightly, maybe, sometimes, becoming.

Allow me an image. Like a convict in front of a firing squad asking to be blindfolded. Allow me, a decent ending, although it’s just the beginning.

We stand in a field of poppies which considering her live-long heroin addiction, is ironic, to say the least. I am six, and whisper, I love you Mommy into her warm neck as she embraces me.

Hush now, she says. Look at the camera and smile. This has to be perfect. Tomorrow we'll leave for America, and it's going to be a long time before we come back. Maybe never. We have to remember our home.

What does that mean, Mommy?

What? Home?

No. To come back?

And "as I held my childhood pictures in my hands, in the tenderness of my 'remembering', I also knew that with each photograph I was forgetting." (Sally Mann, “Hold Still”)

Hold still. Mommy. Come back.

These pictures, these failed images are my cherished deformities, deeper than any of my tattoos, but still not deep enough.

This is why I don't like the word survivor, it falsely presupposes that the abuse could ever end.

But this is not a story of despair, it’s the despair of telling a story. I’ve been writing this for many years. It has shifted in styles, fonts, and languages. For while it even was a poem. But I could never finish. Maybe because the trauma is still there, and probably will never go away, but I keep pretending I will heal, if I can just finish this story. It’s like what a woman in a ridiculous bright sari once said to me on a night bus in Kerela: "Loss and grief aren’t a wound, but a broken bone which will never mend. In order to start walking again, you must change the way you move. You must learn to adjust your body to the damage, not the other way around."

But instead, I go back to Sebald, because for now it just seems like the easiest way out.

The narrator leaves the hospital bed in Norwich, and makes his way to the Lowestoft shore. While en route, he reflects on Thomas Browne who said that all knowledge is enveloped in darkness, and discusses the dissected hand in Rembrandt's “The Anatomy Lesson” as a crass misrepresentation at the exact centre point of meaning. MORE Until finally reaching the beach. An old and outdated photograph of a coastline accompanies the beginning of this chapter. It is motionless, not in the obvious way whereas the figures don’t move, but that they do not emerge. By supplementing the narration with a picture, he seems to confirm the existence of the beach the same way a pipe or a cat can be and not be at the same time, all hamlets aside.

Michael Foucault calls Magritte’s famous pipe ‘that is not’, an unravelled calligram. Traditionally a calligram is a text arranged in such a way, that it forms a thematically related image. How then is the proverbial pipe unravelling? Has the image devoured the text? Or vice versa?

The reader sees as the seer reads, none the wiser for that. Because between that, what can be uttered, and that, what can be seen exists a third dimension. Something inexpressible, yet wickedly tangible, “neither image nor reality, a new being, really: a reality one can no longer touch.”

Foucault claims the words in Magritte’s painting are only reflections of words, they cease to exist in their discursive function, and take upon themselves the visualizing mode of images. This in turn fuses language and representation causing an ontological subterfuge. The moment we understand what is seen and said, the pipe momentarily disintegrates. Not forever, but long enough for our comprehension to be incapacitated. The pipe becomes a ghost, a non-presence. Because death is the actual subject of Magritte’s painting, if not of all images. It's the razor’s edge where “the word is not the thing” (A. Korzybski), and “this is not a story” (D. Diderot). The world of meaning and comprehension, cracks.

One gloomy April Sunday, while i struggled to build a home in London, I decided to visit the Lowestoft beach. I wanted to see what Sebald saw. I wanted to go there, whatever ‘going’ and ‘there’ could possibly mean in this, or any, context. On the train, I thought about going places.

In Roman mythology, Janus was the god of beginnings, transitions, and endings. His effigy presided over passages, doors, and city gates, usually depicted as having two faces each looking in opposite directions. He was the patron of escapes and returns, births, journeys, and change. One of the etymologies indicated by Cicero derived his name from the Latin verb "ire" - to go.

The experience of going places is elusive like the edge of a photograph. Because where do we really go, when we go somewhere? What is where? And more importantly, what happens to the place we leave?

When I arrived on the Lowestoft beach, I realized that neither I, nor Sebald’s narrator could ever, truly have been there. No one can really arrive while traveling, even when one actually does, because all travel, like image-making is pure contingency (Barthes).

As I stood on the surf glued together with the image, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures (Barthes), the beach began to phantom-ize, it suddenly became empty and transparent. Not in the sense of obvious, or easily perceived, but rather like a ghost in a bad horror film: see-through. Although, I was seemingly present in the here of that longed for there, the two aspects of reality switched places, and for a second both disappeared leaving me nowhere. Because, this is not a pipe.

Watching the waves recede into the sea, and then back again I felt foolish to want to be anywhere, to prove anything, be it my own existence, a beach from a novel, the death of my mother, or even the world. The game of arriving is rigged, because, to arrive somewhere is similar to dying. The mystics believe the ideal man shall walk himself to a ‘right death’. He who has arrived ‘goes back’ (Bruce Chatwin, “Songlines”)

Because within any consistent formal system, a statement can be true, but can never be proven within the rules of said system. The Austrian mathematician and philosopher Kurt Gödel proposed this in Königsberg during the Second Conference on the Epistemology of Exact Sciences in 1930, a scientific gathering on matters so profound that they bordered on the esoteric. His findings were later known as the "incompleteness theorems", and changed, not only the way we perceive mathematics, but consequently, reality itself. A formal system of axioms, free of all internal paradoxes and contradictions, will always be incomplete, because it must contain truths and statements that, while being undeniably true, could never be proven within the laws of that system. Similar to an eye which sees everything in front and around it, but can never see itself. These are the limits of human understanding, here we must choose between accepting terrible paradoxes and contradictions, or work with unverifiable truths.

The tent-like shelters on Sebald’s the beach which I desperately wanted to see, were neither inhabited by ghosts, or asylum seekers, but common fishermen from the immediate neighborhood. This meant, they actually did exist in some place and some time, but were absent in the moment of my being there. This conclusion forced me to ask an even more difficult question than 'where do we go when we go somewhere?', namely: how is it that some things are, and others aren’t? Proof generates a far more insidious astonishment than not knowing, it forces us to address “the fundamental question: why is it that I am alive here and now?”

Returning to London on the train I listened to Sufjan Stevens To Be Alone with You. The song lingered in the valleys, piercing me with aching aah’s. Every note, was a shard of glass on which I clumsily walked in order to return home, not knowing what home is. Tucked away behind the sentimental guitar, Sufjan's aah’s carried a shameful and tender shadow. Something holy, but in an entirely unholy way, a precise yearning that drawing a map to a hidden treasure. Animal footprints in the snow haunting the hunter, glimpses of a world not yet reached, or lost, but painfully yearned for in its non-existence.

A world where I am sheltered, taken care of, and anchored.

A world, where I am loved.

And as the last echoes of the song faded merging with the sedated English valleys, a face appeared in the window, and made all this beautiful gravity shift, fade, and fall apart. For a split second something became apparent to me, I saw an image of longing, a dream of closure. I saw a home, and in it, I finally could witness myself as myself.

I tried to whisper my name into the window glass, but as soon as I said it out loud, it recoiled sounding foreign and unspeakable. I've forgotten how to pronounce myself. I've become a shibboleth.

The term originates from the Book of Judges where the Hebrew word shibbólet literally meant the part of a plant containing grain, such as the head of a stalk of wheat, or rye. The Biblical origin story speaks of a battle between two enemy tribes: the Ephraimites and Gileadites. After the former are defeated, the survivors wanted to return home by crossing the river Jordan. But the victors secured its fords, and demanded any person wanting to pass, to pronounce the word: shibboleth.

This was a ruse, the Gileadites knew perfectly well that the Ephraimite dialect had a differently sounding first consonant, and no matter how hard the survivors tried, they could never properly articulate the letter "shin". Thus, they were killed on the spot resulting in one of most horrific genocides recounted in the Bible. And all the survivors wanted, was to return home, but its pivotal sound, had lost its meaning.

Shibboleths were used in many societies throughout history as passwords, or simple ways of proving loyalty and affinity. And like all forms of identification, they very quickly became tools of violence, segregation, and control.

But the true meaning of shibboleth is rooted in translation. In a booklet on Paul Celan, the postmodern philosopher Jacques Derrida invokes the shibboleth as an example of that, what is "unrepeatable" (unwiederholbar), a sort of singularity similar to circumcision, the ritualistic act of getting rid of excess. Like the date at the end of a poem, it is a metaphor of finality.

The word metaphor stems from the Greek term meaning 'to transfer', or 'carry across'. Metaphors transport meaning, they link different things creating new dimensions of understanding. Circumcision is a metaphor for something individual and final, the first and last time. But also, a form of teleology, from the Greek word "telos" meaning ‘end’, ‘aim’, or ‘goal’. It is a place of incision between that which was, and that which can never be again. In this sense, metaphors beside creating new meanings, also sustain the old. They are expressions of attachment a rebours, ways of connecting things and people sustained over time. And like any relation sustained over time, they imply the inevitability of loss. The coherence encapsulating that what can be called the presence of absence.

The paradox of presence of absence expresses change, and is rooted in the instantaneous “sliver of time when something must be both perfectly identical to itself in space and time, so as to be the thing that changes, and somehow different, so as to have changed at all.” In this sense, the rule of similarity warps, almost ceasing to exist altogether.

This is not a pipe, because there is no pipe. We can never return, and the shibboleth always remains a mystery, “an uncertain passage”.

My mother's death became a shibboleth when I tried to understand it. Like a date, it circumcised my life both with a sense of uniqueness and finality. Because a date doesn’t only refer to time, but also to space, and how certain events warp it. The thing a date signalizes can never return, because it is caught in an endless cycle of constant returns, like the pipe, that is not. If it does return, it can only do so in itself, entangled like fingerprints which on the one hand (sic!) testify to our individual identity, while on the other, form an endless cycle of repetition.

The shibboleth is not a password, it is the opposite, a never-ending access. Similar to Schwarzschild's singularity, were it ever to be experienced by humans, it would endure until the end of the universe, simply because there would be no concept of an end, to end it. Like the rings of a tree, or Saturn.

The rings of Saturn describe circular orbits around the planet's equator. They consist of ice crystals, and in all likelihood, fragments of a former moon that got too close to the planet and was destroyed by its tidal effect. A tidal force, or tidal-generating force, is a gravitational effect that stretches a body along the line towards, and away from the center of the mass of another body. It is makes waves, and in extreme cases, is responsible for the spaghettification of objects. It arrises, because the gravitational field exerted on one body by another is not constant across its parts: the nearer side is attracted more strongly than the farther side causing the body to stretch. The mass of the earth generates a tide that cuts the surface of the moon, just as the moon itself gives rise to the ocean tides. While the later is liquid and brings forth change, the former forms a wave of solid rock four meters high over the moon's crust, an ever-growing mountain which is unmovable locking everything in place.

Saturn's tidal theory was originally proposed by Edouard Roche in the 19th century. He named the obliterated moon Veritas, after the Roman goddess said to have hidden in the bottom of a holy well. She was often depicted both as a virgin dressed in white, and as the "naked truth" holding a mirror to reality. Numerical simulations carried out in 2022 support this theory, but its authors proposed a different name for the destroyed moon. They called it "Chrysalis", after the pupa stage of a butterfly. Whereas, the last stage of a butterfly's life, is called "imago".

Schwarzschild died of pemphigus, a disease in which the body fails to recognize its own cells, and attacks them violently. While still at school, he calculated the equilibrium of liquid bodies in rotation, desperately trying to prove the long-term stability of the rings of Saturn which he saw coming apart over and over in a recurring nightmare.

At first, you might think it’s only a scratch, nothing to worry about, just a little crack in the floor. But when you look further ahead you realize it doesn't stop, it grows bigger and bigger, until utterly devouring the space. When commissioned to fill the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern, Salcedo made a shibboleth. She once said that, "memory must work between the figure of the one who has died and the one disfigured by this death”, and so she defaced Tate Modern, and consequently London, because it's not the bullet that kills you, but the hole .

The act of cutting is often motivated by anger, by an inexplicable need to harm oneself, or others in order to regain control. Abused children do this all the time. But Salcedo's anger wasn’t directed at any person in particular, it wasn’t focused on who did the harm per se, but how and where it surfaced. The space of culture and society isolates those who do not fit in. They are locked up in ghettos, displaced, or simply disappeared. Her cut exposes the unseen, creating a moment of disjuncture, both literally and metaphorically. A cut unearths that, what lies beneath, it uncovers the missing link, the repressed, forgotten, and ignored. Salcedo's Tate Modern Unilever installation pulls London apart. It shows how the space of the city, but also ‘civilization’, is essentially broken.

The tear in Tate Modern was a spatial reminder to all the visitors who delight in the views across the river of the City of London with its architect-designed skyscrapers, Victorian chapels and exquisite town houses attesting to wealth and power, that behind those glossy exteriors exists the windowless backings of the less respectable area of South London, traditionally home to immigrants, the poor and discarded. In this sense, Salcedo's work is a brutal doubling of the Thames, which for centuries had been a natural urban shibboleth, dividing the city into presence and absence, visibility and obscurity, privilege and hindrance. As Mieke Bal accurately put it: "the result of her intervention is a negative space, an emptiness not remedied but exacerbated; a space cut into two halves that are each other's negatives”.

I will never understand my mother’s death, although I so ceaselessly try to describe it. But through it, I hope I can understand myself.

When words upset their designates, the connotations unravel, and the pivotal “shin” of meaning evaporates. Safe passage towards identification and meaning is lost. The space, where description and image meet, is ripped apart, and we enter the event horizon of images.

This is where their treachery begins.

And this is where, I search for my home.

After leaving the fishermen of the Lowestoft coast, Sebald’s narrator recalls a “flickering short film used in primary school as a popular didactic model of the indestructibility of Nature” which re-presented a trawler fishing for herring in almost total darkness. “By night, it appeared, the nets were cast, and by night they were hauled in again.”

Once more the narrator tricks us, because what he sees and describes, is not the thing itself, but the memory of an image of the thing. He proceeds to recall the herring’s biography, beginning with the fish’s morphology (“an idiosyncrasy peculiar to the herring is that, when dead, it begins to glow”), psychology (“the truth is that we do not know what the herring feels”), and how two English scientist in the late XIX century wanted to use the dead bodies of herrings to illuminate British cities. He meanders a bit boringly through the story of Major George Wyndham Le Strange, who left his vast estate to “the housekeeper to whom he hardly spoke for over thirty years”, and then, suddenly, stuns the reader-viewer seemingly out of nowhere, with a twofold photograph of hundreds of bodies from the death camp in Bergen Belsen. He never explains the reason for adding this picture, nor does he comment on its significance for the story. The only link, is that Le Strange served in the anti-tank regiment that liberated the camp in 1945. He leaves us guessing as to the meaning of the image casually lingering in our imagination between heaps of herrings, scales, and street lamps.

Because, this is not a pipe. Or maybe, it actually is, but not the sort of pipe we expect.

Nests weren’t things that were made to be found. They were carefully maintained blind spots, redacted lines in familiar texts.

Helen Mcdonald, “Vesper Flights”

René Magritte, The Human Condition (1933)Which is how we see the world, namely, outside of us; although having only one representation of it within us. Similarly we sometimes remember a past event as being in the present. Time and space lose meaning and our daily experience becomes paramount. This is how we see the world. We see it outside ourselves, and at the same time we only have a representation of it in ourselves. In the same way, we sometimes situate in the past that which is happening in the present.

René Magritte in a letter to the Belgian poet Achille Chaveé

Whoever leads a solitary life and yet now and then wants to attach himself somewhere, whoever, according to changes in the time of day, the weather, the state of his business, and the like, suddenly wishes to see any arm at all to which he might cling - he will not be able to manage for long without a window looking on to the street.

Franz Kafka, “The Street Window”

Jeff Wall, Blind Window No. 1 (2000)Jeff Wall, Blind Window No. 2 (2000)In the spatial sense, the grid states the autonomy of the realm of art. Flattened, geometricized, ordered, it is antinatural, antimimetic, antireal. It is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature. (…) Insofar as its order is that of pure relationship, the grid is a way of abrogating the claims of natural objects to have an order particular to themselves; the relationships in the aesthetic field are shown by the grid to be in a world apart and, with respect to natural objects, to be both prior and final. The grid declares the space of art to be at once autonomous and autotelic.

Rosalind Krauss, “Grids”

Jeff Wall, Blind Window No. 3 (2000)An image of the core region of Messier 87, a supermassive black hole, processed from a sparse array of radio telescopes known as the EHT with colors indicating brightness temperature.I don't know how to name or define it, but it has an irrepressible force and darkens my thoughts. It is a void without form or dimension, a shadow I can't see, but one that I can feel with the entirety of my soul.

Karl Schwarzschild

Ultimately - or at the limit - in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes. ‘The necessary condition for an image is sight,’ Janouch told Kafka; and Kafka smiled and replied: ‘We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds. My stories are a way of shutting my eyes.’

Roland Barthes, “Camera Lucida“

From the footpath that runs along the grassy dunes and low cliffs one can see, at any time of the day or night and at any time of the year, as I have often found, all manner of tent-like shelters made of poles and cordage, sailcloth and oilskin, along the pebble beach. They are strung out in a long line on the margin of the sea, at regular intervals. It is as if the last stragglers of some nomadic people had settled there, at the outermost limit of the earth, in expectation of the miracle longed for since time immemorial, the miracle which would justify all their erstwhile privations and wanderings.

W. G. Sebald, “Rings of Saturn”

(…) to this day there is something illusionistic and illusory about the relationship of time and space as we experience it in traveling, which is why whenever we come home from elsewhere we never feel quite sure if we have really been abroad.

W. G. Sebald, “Austerlitz”

Then (so says the booklet accompanying the 1936 trawler film), the railway goods wagons take in this restless wanderer of the seas and transport it to those places where its fate on this earth will at last be fulfilled.

W. G. Sebald, “Rings of Saturn”